the ape that took over the world

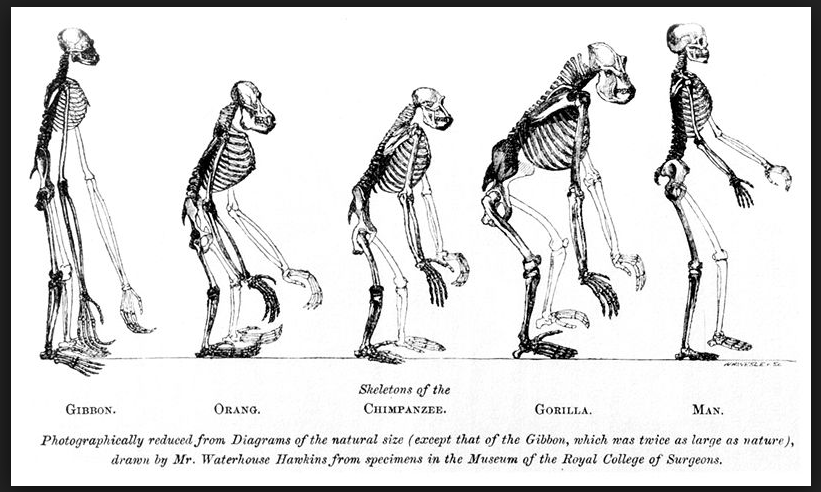

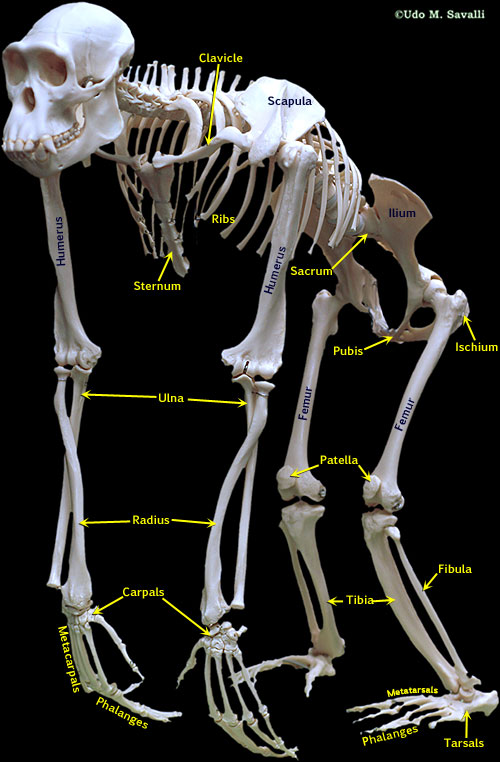

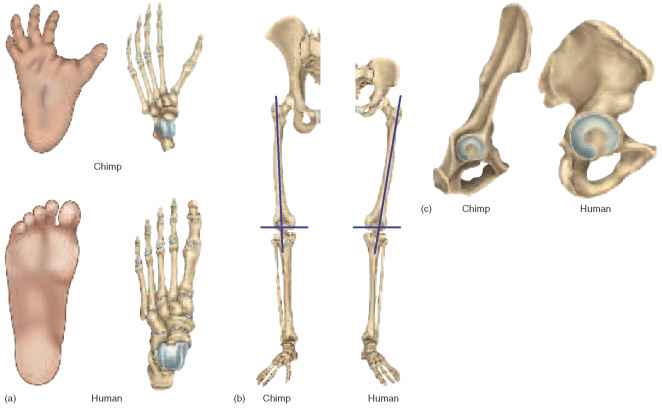

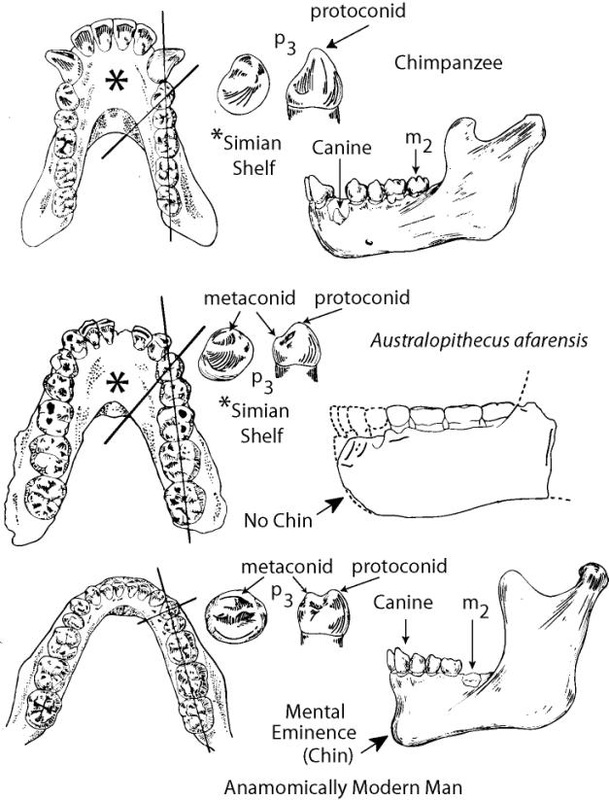

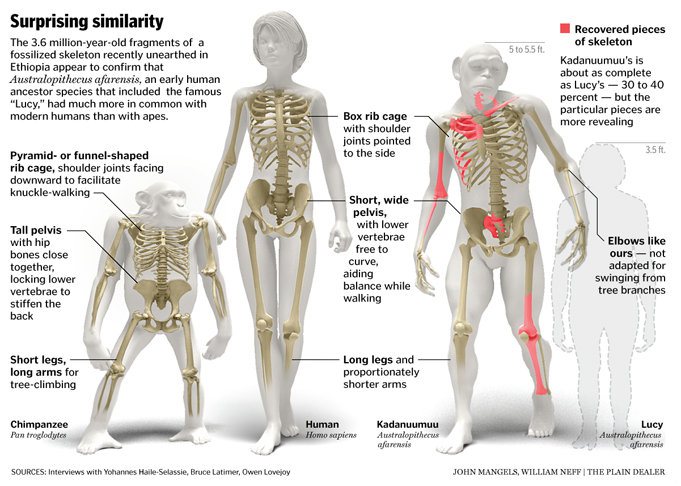

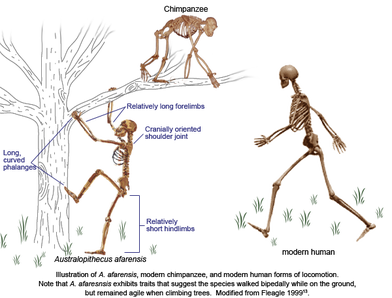

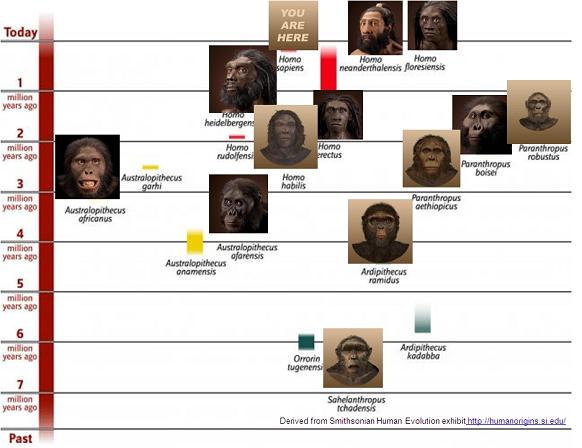

The footprints at Laetoli are just part of the fossil evidence that depicts human evolution. In 1974, paleontologist Don Johanson’s team discovered the skeleton of Lucy, now known as Australopithecus afarensis. Lucy’s skeleton was clearly different from other primates. Her knees could lock, her femur slanted inward, and her large toe was in line with her other toes, allowing her to walk upright. The discovery of Lucy surprised paleontologists because although she was unquestionably bipedal, she was remarkably apelike—with a brain about the size of a chimpanzee’s. Bipedalism is a tremendous adaptation for humans and a distinguishing characteristic between humans and other primates. There are many hypotheses about the advantages of bipedalism, including the ability to carry food from place to place, to walk long distances efficiently, the freeing of hands for tool use, and the ability to see further or more clearly during travel. Any or all of these hypotheses may be correct and are being explored by anthropologists today.

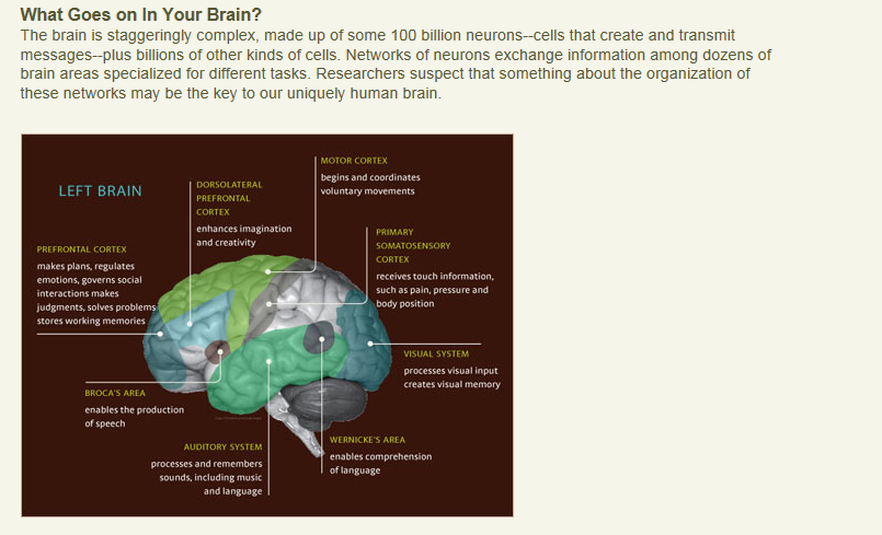

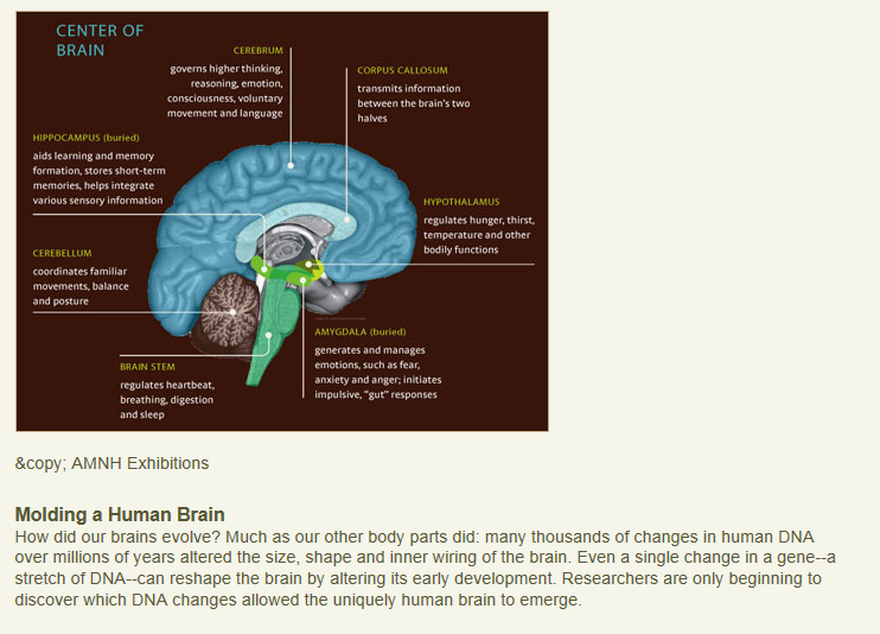

The human brain

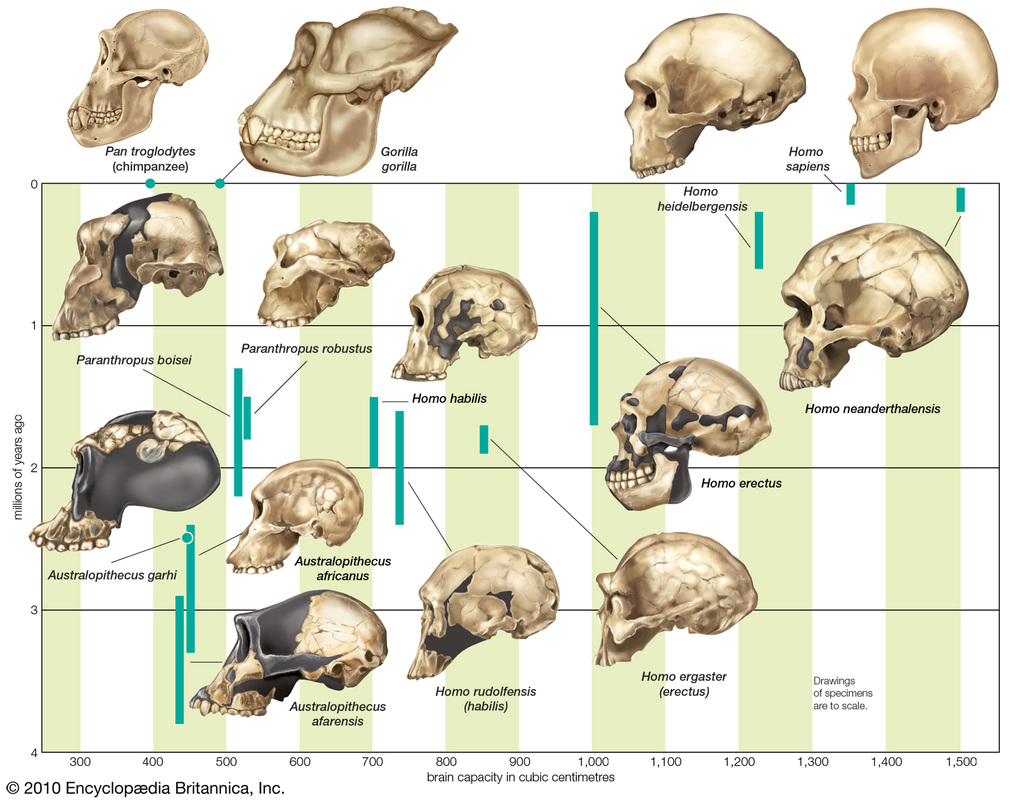

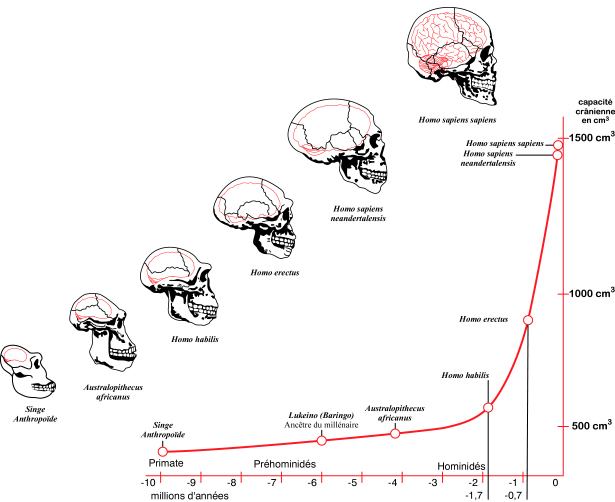

A second major adaptive advantage that appeared later in human evolution was an increase in brain size. Fossil evidence

allows us to trace the development of the brain as it increased threefold over the last 3 million years. Early hominids such as

the australopithecines had brains the size of modern apes (400 to 500cc). Homo habilis, with a brain of about 650cc, was probably the first hominid to make and use stone tools. As brain size increased new capabilities evolved, improving the ability of hominids to adapt to and modify their environments.

The earliest evidence of the use of tools to modify or manipulate objects and elements of the environment is seen in Homo habilis. This is the same time that we observe an increase in brain size in both absolute terms and relative to body size. Australopithecines had absolute and relative brain sizes not greatly different from those of the modern apes. In comparison, the brain size of the Homo lineage showed an exponential increase from H.habilis onwards (Fig 3).

Brain size is not inherently linked to evolutionary success. The Neanderthal brain had a larger volume than the modern human brain, yet was not as successful. Indeed, brains are energetically expensive and there are many large animals with highly successful volutionary histories yet relatively small brains (witness the dinosaur prior to the asteroid‐induced extinction). Thus the question of why hominins evolved large brains and Homo sapiens is endowed with its unique set of capacities is not self‐evident. There are several inter‐related theories on the evolutionary origin of

brain expansion. Effectively they either place emphasis on Homo species finding adaptive advantage in social interactions within their group, or in planning their affairs for hunting and tool making. The weight of evidence now favours the former.

The reproductive cost of brain expansion

The development of the large brain had other consequences for hominins. Most significant being the problems associated with giving birth to a baby with a large head through the narrow and rigid birth canal that arose as a result of the pelvic changes associated with bipedalism. If the human infant was born at the same stage of maturity as other primates, then pregnancy would last about 21 months: this would require a pelvic canal so wide that it would be impractical for efficient bipedal locomotion. The compromise has been that humans give birth to an infant at a stage when the head can fit through the birth canal, but this means that the human infant is entirely dependent on its mother for many months after birth. This need to give birth to a totally dependent infant has determined human social structure—if the mother is to support the infant she in turn needs to be confident of support from the father. Thus while early hominids showed great sexual dimorphism, with the males much larger than the females, implying a harem type mating system with fighting between males for mating rights, Homo sapiens has a much lesser degree of sexual dimorphism, suggesting that in general females were able to have continued support from one male.

allows us to trace the development of the brain as it increased threefold over the last 3 million years. Early hominids such as

the australopithecines had brains the size of modern apes (400 to 500cc). Homo habilis, with a brain of about 650cc, was probably the first hominid to make and use stone tools. As brain size increased new capabilities evolved, improving the ability of hominids to adapt to and modify their environments.

The earliest evidence of the use of tools to modify or manipulate objects and elements of the environment is seen in Homo habilis. This is the same time that we observe an increase in brain size in both absolute terms and relative to body size. Australopithecines had absolute and relative brain sizes not greatly different from those of the modern apes. In comparison, the brain size of the Homo lineage showed an exponential increase from H.habilis onwards (Fig 3).

Brain size is not inherently linked to evolutionary success. The Neanderthal brain had a larger volume than the modern human brain, yet was not as successful. Indeed, brains are energetically expensive and there are many large animals with highly successful volutionary histories yet relatively small brains (witness the dinosaur prior to the asteroid‐induced extinction). Thus the question of why hominins evolved large brains and Homo sapiens is endowed with its unique set of capacities is not self‐evident. There are several inter‐related theories on the evolutionary origin of

brain expansion. Effectively they either place emphasis on Homo species finding adaptive advantage in social interactions within their group, or in planning their affairs for hunting and tool making. The weight of evidence now favours the former.

The reproductive cost of brain expansion

The development of the large brain had other consequences for hominins. Most significant being the problems associated with giving birth to a baby with a large head through the narrow and rigid birth canal that arose as a result of the pelvic changes associated with bipedalism. If the human infant was born at the same stage of maturity as other primates, then pregnancy would last about 21 months: this would require a pelvic canal so wide that it would be impractical for efficient bipedal locomotion. The compromise has been that humans give birth to an infant at a stage when the head can fit through the birth canal, but this means that the human infant is entirely dependent on its mother for many months after birth. This need to give birth to a totally dependent infant has determined human social structure—if the mother is to support the infant she in turn needs to be confident of support from the father. Thus while early hominids showed great sexual dimorphism, with the males much larger than the females, implying a harem type mating system with fighting between males for mating rights, Homo sapiens has a much lesser degree of sexual dimorphism, suggesting that in general females were able to have continued support from one male.

2. Getting to know the relatives

Read chapter 20- to discover the characteristics of austarlopithecines.

Read chapeter 21- to discover the characteristics of the Homo species.......cultural evolution in on the rise......and with nthat further biological evolution

Read chapeter 21- to discover the characteristics of the Homo species.......cultural evolution in on the rise......and with nthat further biological evolution

check out this interactive timeline: http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-evolution-timeline-interactive

homo erectus

neanderthal

3. Hominin Evolution- Homo sapiens

Read chapter 22- look at the typical characteristics of H.sapiens, their technologies, migration pathways, lifestyle and the more recent cultural evolution.

tools...

O L D O W A NOldowan tools are the oldest known, appearing first in the Gona and Omo Basins in Ethiopia about 2.4 million years ago. They likely came at the end of a long period of opportunistic tool usage: chimpanzees today use rocks, branches, leaves and twigs as tools. The key innovation is the technique of chipping stones to create a chopping or cutting edge.

Most Oldowan tools were made by a single blow of one rock against another to create a sharp-edged flake. The best flakes were struck from crystalline stones such as basalt, quartz or chert, and the prevalence of these tools indicates that early humans had learned and could recognize the differences between types of rock. Typically many flakes were struck from a single "core" stone, using a softer spherical hammer stone to strike the blow. These hammer stones may have been deliberately rounded to increase toolmaking control. Flakes were used primarily as cutters, probably to dismember game carcasses or to strip tough plants. Fossils of crushed animal bones indicate that stones were also used to break open marrow cavities. And Oldowan deposits include pieces of bone or horn showing scratch marks that indicate they were used as diggers to unearth tubers or insects. Currently, all these tools are associated with Homo habilis (rudolfensis) only; if the robust australopithecines used tools, they were apparently not shaped stones.

A C H E U L E A N The Acheulean tool industry first appeared around 1.5 million years ago in East Central Africa. These tools are associated with Homo ergaster and western Homo erectus. The key innovations are (1) chipping the stone from both sides to produce a symmetrical (bifacial) cutting edge, (2) the shaping of an entire stone into a recognizable and repeated tool form, and (3) variation in the tool forms for different tool uses. Manufacture shifted from flakes struck from a stone core to shaping a more massive tool by careful repetitive flaking. The most common tool materials were quartzite, glassy lava, chert and flint. Making an Acheulean tool required both strength and skill. Large shards were first struck from big rocks or boulders. These heavy blades were shaped into bifaces, then refined at the edges (using bone or antler tools) into distinctive variations in shape — referred to by paleoanthropologists as axes, picks, and flat edged cleavers. About 1.0 million years ago, symmetrical, teardrop or lanceolate shaped blades (so called hand axes) begin appearing in Acheulean deposits. Some of these "hand" axes are extremely large and may possibly have had a ceremonial or monetary function; or they may have been used for very heavy work such as butchering large animals or milling branches or trees into fire fuel. Either way, their size suggests both a more complex technology and a more interdependent group structure.

M O U S T E R I A N The Mousterian industry appeared around 200,000 years ago and persisted until about 40,000 years ago, in much the same areas of Europe, the Near East and Africa where Acheulean tools appear. In Europe these tools are most closely associated with Homo neanderthalensis, but elsewhere were made by both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens. Mousterian tools required a preliminary shaping of the stone core from which the actual blade is struck off. The toolmakers either shaped a rock into a rounded surface before striking off the raised area as a wedge shaped flake (see photo at left), or they shaped the core as a long prism of stone before striking off triangular flakes from its length, like slices from a baguette. Because Mousterian tools were conceived as refinements on a few distinct core shapes, the whole process of making tools had standardized into explicit stages (basic core stone, rough blank, refined final tool). Variations in tool shapes could be produced by changes in the procedures at any stage. A consistent manufacturing goal was to increase as much as possible the cutting area on each blade. Though this made the toolmaking process more labor intensive, it also meant the edges of the tools could be reshaped or sharpened as they dulled, so that each tool lasted longer. The whole toolmaking industry had adapted to get the maximum utility from the labor invested at each step. Tool forms in the Mousterian industry display a wide range of specialized shapes. Cutting tools include notched flakes, denticulate (serrated) flakes, and flake blades similar to Upper Paleolithic tools. Points appear that seem designed for use in spears or lances, some including a tang or stub at the base that allowed the point to be tied into the notched end of a stick. Scrapers appear for the dressing of animal hides, which were probably used for shoes, clothing, bedding, shelter, and carrying sacks. These accumulating material possessions imply a level of social organization and stability comparable to primitive humans today. Because tools were combined with other components (handles, spear shafts) and used in wider applications (dressing hides, shaping wood tools, hunting large game), Mousterian technology was the keystone for many interrelated manufacturing activities in other materials: specialized tools created specialized labor. As these activities evolved and standardized, the efficient and flexible Mousterian toolmaking procedures made possible the accumulation of physical comforts on which wealth and social status are based.

P P E R P A L E O L I T H I C The Upper Paleolithic industry, dominant from 40,000 to 12,000 years ago, appears to have originated independently in both Asia and (as early as 90,000 years ago) in Africa. This toolmaking culture shows a remarkable proliferation of tool forms, tool materials, and much greater complexity of toolmaking techniques. It also quickly diversified into distinctive regional styles, some of which appear as sequentially overlapping but esthetically recognizable toolmaking cultures. These adaptations in tool forms respond to the increased range of material tasks that appeared in the Mousterean industry. Regional styles are probably not just stylistic variations but reflect the adaptation of tools to different materials and the manufacturing requirements of different habitats, different food sources, and a corresponding increase in the size of human habitations. It is, for example, in the Upper Paleolithic industry that sewing needles and fish hooks first appear. The geographically extensive Aurignacian period (40,000 to 28,000 years ago) is associated with both Homo sapiens (Cro Magnon) and Homo neanderthalensis throughout Europe and parts of Africa. The more limited Châtelperronian (40,000 to 34,000 years ago) is a variant of the Aurignacian principally associated with the declining tribes of European Homo neanderthalensis in Europe. After Neanderthals went extinct, the Gravettian period (28,000 to 22,000 years ago) added backed blades and bevel based bone points to the tool repertory. Ivory beads turn up as burial ornaments, and ritual "Venus figurines" appear. Ritual and religion were added to the wealth and status hierarchies of human culture. The brief Solutrean period (22,000 to 19,000 years ago) introduced very elegant tool designs made possible by heating and suddenly cooling flint stones to shatter them in carefully controlled ways.

Most Oldowan tools were made by a single blow of one rock against another to create a sharp-edged flake. The best flakes were struck from crystalline stones such as basalt, quartz or chert, and the prevalence of these tools indicates that early humans had learned and could recognize the differences between types of rock. Typically many flakes were struck from a single "core" stone, using a softer spherical hammer stone to strike the blow. These hammer stones may have been deliberately rounded to increase toolmaking control. Flakes were used primarily as cutters, probably to dismember game carcasses or to strip tough plants. Fossils of crushed animal bones indicate that stones were also used to break open marrow cavities. And Oldowan deposits include pieces of bone or horn showing scratch marks that indicate they were used as diggers to unearth tubers or insects. Currently, all these tools are associated with Homo habilis (rudolfensis) only; if the robust australopithecines used tools, they were apparently not shaped stones.

A C H E U L E A N The Acheulean tool industry first appeared around 1.5 million years ago in East Central Africa. These tools are associated with Homo ergaster and western Homo erectus. The key innovations are (1) chipping the stone from both sides to produce a symmetrical (bifacial) cutting edge, (2) the shaping of an entire stone into a recognizable and repeated tool form, and (3) variation in the tool forms for different tool uses. Manufacture shifted from flakes struck from a stone core to shaping a more massive tool by careful repetitive flaking. The most common tool materials were quartzite, glassy lava, chert and flint. Making an Acheulean tool required both strength and skill. Large shards were first struck from big rocks or boulders. These heavy blades were shaped into bifaces, then refined at the edges (using bone or antler tools) into distinctive variations in shape — referred to by paleoanthropologists as axes, picks, and flat edged cleavers. About 1.0 million years ago, symmetrical, teardrop or lanceolate shaped blades (so called hand axes) begin appearing in Acheulean deposits. Some of these "hand" axes are extremely large and may possibly have had a ceremonial or monetary function; or they may have been used for very heavy work such as butchering large animals or milling branches or trees into fire fuel. Either way, their size suggests both a more complex technology and a more interdependent group structure.

M O U S T E R I A N The Mousterian industry appeared around 200,000 years ago and persisted until about 40,000 years ago, in much the same areas of Europe, the Near East and Africa where Acheulean tools appear. In Europe these tools are most closely associated with Homo neanderthalensis, but elsewhere were made by both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens. Mousterian tools required a preliminary shaping of the stone core from which the actual blade is struck off. The toolmakers either shaped a rock into a rounded surface before striking off the raised area as a wedge shaped flake (see photo at left), or they shaped the core as a long prism of stone before striking off triangular flakes from its length, like slices from a baguette. Because Mousterian tools were conceived as refinements on a few distinct core shapes, the whole process of making tools had standardized into explicit stages (basic core stone, rough blank, refined final tool). Variations in tool shapes could be produced by changes in the procedures at any stage. A consistent manufacturing goal was to increase as much as possible the cutting area on each blade. Though this made the toolmaking process more labor intensive, it also meant the edges of the tools could be reshaped or sharpened as they dulled, so that each tool lasted longer. The whole toolmaking industry had adapted to get the maximum utility from the labor invested at each step. Tool forms in the Mousterian industry display a wide range of specialized shapes. Cutting tools include notched flakes, denticulate (serrated) flakes, and flake blades similar to Upper Paleolithic tools. Points appear that seem designed for use in spears or lances, some including a tang or stub at the base that allowed the point to be tied into the notched end of a stick. Scrapers appear for the dressing of animal hides, which were probably used for shoes, clothing, bedding, shelter, and carrying sacks. These accumulating material possessions imply a level of social organization and stability comparable to primitive humans today. Because tools were combined with other components (handles, spear shafts) and used in wider applications (dressing hides, shaping wood tools, hunting large game), Mousterian technology was the keystone for many interrelated manufacturing activities in other materials: specialized tools created specialized labor. As these activities evolved and standardized, the efficient and flexible Mousterian toolmaking procedures made possible the accumulation of physical comforts on which wealth and social status are based.

P P E R P A L E O L I T H I C The Upper Paleolithic industry, dominant from 40,000 to 12,000 years ago, appears to have originated independently in both Asia and (as early as 90,000 years ago) in Africa. This toolmaking culture shows a remarkable proliferation of tool forms, tool materials, and much greater complexity of toolmaking techniques. It also quickly diversified into distinctive regional styles, some of which appear as sequentially overlapping but esthetically recognizable toolmaking cultures. These adaptations in tool forms respond to the increased range of material tasks that appeared in the Mousterean industry. Regional styles are probably not just stylistic variations but reflect the adaptation of tools to different materials and the manufacturing requirements of different habitats, different food sources, and a corresponding increase in the size of human habitations. It is, for example, in the Upper Paleolithic industry that sewing needles and fish hooks first appear. The geographically extensive Aurignacian period (40,000 to 28,000 years ago) is associated with both Homo sapiens (Cro Magnon) and Homo neanderthalensis throughout Europe and parts of Africa. The more limited Châtelperronian (40,000 to 34,000 years ago) is a variant of the Aurignacian principally associated with the declining tribes of European Homo neanderthalensis in Europe. After Neanderthals went extinct, the Gravettian period (28,000 to 22,000 years ago) added backed blades and bevel based bone points to the tool repertory. Ivory beads turn up as burial ornaments, and ritual "Venus figurines" appear. Ritual and religion were added to the wealth and status hierarchies of human culture. The brief Solutrean period (22,000 to 19,000 years ago) introduced very elegant tool designs made possible by heating and suddenly cooling flint stones to shatter them in carefully controlled ways.

Human dispersal

|

|

|

who am i?

|

Thi is cool see VIDEO

|

revision

Bbc radio-listen up:

The Neanderthals (45 minutes)

Are we still Evolving Part 1 (30 min)

Are we still Evolving Part 2 (30 min)

Are we still Evolving Part 1 (30 min)

Are we still Evolving Part 2 (30 min)